French New Wave: the “look”

-

Shot on Location.

-

Used lightweight, hand-held cameras.

-

Lightweight sound & lighting equipment.

-

Faster film stocks, less light.

-

Films shot quickly and cheaply.

-

Encouraged:

-

– experimentation

-

– improvisation.

-

– experimentation

-

Casual, natural look;

-

Available light;

-

Available sound;

-

Mise-en-scene – French landscape, cafés;

-

Mobile camera – improvised & innovative.

1940 - 1944: The Occupation

Paris during the Second World War was a dark city. The blackout imposed by the occupying German forces meant that lights had to be turned off, a shortage of petrol kept cars off the road, while a curfew kept most people off the streets at night. During the day, numerous regulations, censorship and propaganda, made the occupation increasingly unbearable.

Paris during the Second World War was a dark city. The blackout imposed by the occupying German forces meant that lights had to be turned off, a shortage of petrol kept cars off the road, while a curfew kept most people off the streets at night. During the day, numerous regulations, censorship and propaganda, made the occupation increasingly unbearable.

One of the few distractions available to the French citizens was the cinema, but the choice of what to see was limited. American films were banned, and aside from German productions which consisted mainly of imitations of Hollywood musical comedies and melodramatic propaganda movies, they only had access to the 200 odd French films that were produced during this four year period. These films, which had to be approved by the German censor, were, with a few exceptions, pale imitations of the great French cinema of Marcel Carne, Rene Clair, Marcel Pagnol, and Jean Renoir that had come before the war.

Le Corbeau (The Raven) [1943]

To a generation of cinephiles like Andre Bazin, Alain Resnais and Eric Rohmer, who had grown up in the rich cinematic culture of the 1920’s and 30’s, this lack of choice added to the sense of loss they already felt as a consequence of the war. And it wasn’t just French films they missed, they could also no longer see the American genre films they loved: westerns, comedies and adventure films by directors such as Howard Hawks, Josef von Sternberg, Leo McCarey and Ernst Lubitsch. This experience of loss led them to prize freedom of expression and truth of representation above all else; values which would become central to their later work.

For a younger generation born around 1930, who would later make up most of the directors of the New Wave, the cinema became the centre of their universe and a refuge from the harsh reality of the world outside. They were too young to know very much about the films that had come before the war, and had no reviews or criticism to guide them, but they instinctively cherished a handful of films made during the occupation like Lumiere d’ete (1943) by Jean Gremillon, Les Visiteurs du Soir (1943) by Carne and Prevert, Le Destin Fabuleux de Disiree Clary (1941) by Sacha Guitry, Goupi Mains Rouges (1943) by Jacques Becker, and above all, Le Corbeau (1943) by Henri-Georges Clouzot.

France After The War

In 1944 France was liberated from German Occupation by the Allied forces. In the years that followed the Liberation, cinema become more popular than ever. French films such as Marcel Carne’s Les Enfants du paradise (1945) and Rene Clement’s La Bataille du Rail (1946) were a great success. Italian and British imports were also popular. Most popular of all were the stockpile of films now streaming in from Hollywood.

During the occupation the Nazis had banned the import of American films. As a result, after the war, when the ban was lifted by the 1946 Blum-Byrnes agreement, nearly a decade’s worth of missing films arrived in French cinemas in the space of a single year. It was a time of exciting discoveries for cine-philes eager to catch up with what had been happening in the rest of the world.

Reviews and Journals

Andre Bazin

The Liberation brought with it a great desire for self-expression, open communication and understanding. The discussion of film, inevitably, became part of the discourse. Journals, such as L’EcranFrancais, became a platform for writers like Andre Bazin to develop their theories and convey their enthusiasm for film. Bazin saw cinema as an art form, and one that deserved serious analysis. His interest was in the language of film – favouring the discussion of form over content. Such an attitude tended to bring him into conflict with the predominantly left wing writers at the paper, who were more concerned with the political standpoint of a film.

Another writer at the magazine who shared Bazin’s sense of aesthetics was Alexandre Astruc. In 1948 he wrote an article titled “Birth of a New Avant-Garde: The Camera as Pen”, in which he argued for cinema, like literature, to become a more personal form, in which the camera literally became a pen in the hands of a director. The article would become something of a manifesto for the New Wave generation and a first step in the development of “auteur theory”.

Another popular magazine amongst cinephiles was Le Revue du Cinema. This was a publication devoted to the arts and therefore much less concerned with politics and issues of social commitment. American cinema was discussed as much as European cinema and there were in depth studies of directors like D.W. Griffith, John Ford, Fritz Lang and Orson Welles. Andre Bazin contributed some important articles to the magazine on cinema technique, as did the young Eric Rohmer, whose piece, “Cinema, the art of Space” would have a lasting influence on the directors of the New Wave.

Film Clubs

The same enthusiasts who avidly read the film journals now began setting up film clubs, not just in Paris, but all over France. The most famous of these was Henri Langlois’ Cinematheque Française, which first opened its doors in 1948. The cinema, which he co-founded with Georges Franju, was small, consisting of just 50 seats, but the programme of films shown was both comprehensive and eclectic, and it soon became a mecca for serious film enthusiastsHenri Langlois

Langlois believed the Cinematheque was a place for learning, not just watching, and he wanted his audience to really understand what they were seeing. It became his practice to screen films on the same evening, that were different in style, genre and country of origin. Sometimes he would show foreign films without translation or silent films without musical accompaniment. This approach, he hoped, would focus the audience attention on the techniques behind what they were watching, and the links connecting films that might otherwise appear very different.

It was here, at the Cinematheque, that many of the important figures of the New Wave first met. Francois Truffaut, only sixteen, was already a veteran film-goer. From a young age, the cinemas of Paris had been his refuge from an unhappy home life. He had even set up his own cine-club, Le Cercle Cinemane, although it only lasted for one session. Jean-Luc Godard was another who immersed himself in the cine-clubs. He was studying ethnology at the Sorbonne when he first started going to the Cinematheque, and, for him too, cinema became something of a refuge. He later wrote that the cinema screen was “the wall we had to scale to escape from our lives.”

Alain Resnais, Jacques Rivette, Claude Chabrol, Roger Vadim, Pierre Kast, and others who would later become directors, received much of their film education at film clubs like the Cinematheque and The Cine-Club du Quartier Latin. For true cine-philes like these, watching films was only part of the experience. They would also collect stills and posters, read and discuss the latest film articles and make lists of favourite directors. It was all a way of putting what they were watching into some kind of perspective and developing their own critical viewpoints.

Another avid member of the cine-club audience was Eric Rohmer. He had already published articles in other film journals, and now, with his two friends Jacques Rivette and Jean-Luc Godard, he set up his own review called La Gazette Du Cinema. Although the paper only had a small circulation, it was a means by which they could express their views on some of the films they were watching. Others likeTruffaut and Resnais soon followed, writing articles for magazines like Arts and Les Amis du Cinema.

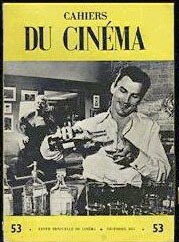

Cahiers du Cinema

The most important and popular film journal of all first appeared in 1951. Set up by Jacques Doniol-Valcrozeand Andre Bazin out of the ashes of the La Revue du Cinema, which had closed down the previous year, it was called Les Cahiers du Cinema. The first issues of the review, with its distinctive yellow cover, featured the best critics of the time writing scholarly articles about film. However, it was with the arrival of a younger generation of critics, including Rohmer, Godard, Rivette, Claude Chabrol and Francois Truffaut, that the paper really began to make waves.

Bazin had become something of a father figure to these young critics. He was especially close to Truffaut, helping to secure his release from the young offenders institute where he was sent as a teenager, and later from the army prison where he was locked up for desertion. At first, Bazin and Doniol-Valcroze allowed the young cine-philes a small amount of column space to air their often combative opinions, but, in time, their articles gained more and more attention and their status rose accordingly.Francois Truffaut

...

One thing these young writers shared was a disdain for the mainstream "tradition de qualite", which dominated French cinema at the time. In 1953, Truffaut wrote an essay for Cahiers entitled "A Certain Tendency of the French Cinema", in which he virulently denounced this tradition of adapting safe literary works, and filming them in the studio in an old fashioned and unimaginative way. This style of cinema wasn’t visual enough, Truffaut argued, and relied too much on the screenwriter. He and the others labelled it ‘cinema de papa’, and compared it unfavourably with the work of film-makers from elsewhere in the world.

Bazin delayed the article’s release for a year, fearing they would lose readers and anger the film-makers who were being attacked. When it was eventually published it did cause offence but there was also considerable agreement. The passionate and irreverent style of Truffaut’s writing, like that of the other young critics, was a shift away from the hitherto austere tone of Cahiers. It brought the journal both a notoriety and popularity it hadn’t had before. Now he, Rohmer, Godard, Rivette, and Chabrol, were given the opportunity to promote their favourite directors within the review and develop their theories.

Favourite Directors

Henri Langlois always believed that watching silent films was the best way to learn the art of cinema, and he frequently included films from this period in the Cinematheque Français programme. As a result the new wave group had a great respect for directors like D.W. Griffith, Victor Sjostrom, Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin, and Erich von Stroheim, who had pioneered the techniques of filmmaking in its early years. When they began making films themselves, silent movies would continue to be a source of inspiration for the New Wave directorsFritz Lang

Three German directors, Ernst Lubitsch, Fritz Lang and F.W. Murnau, were held in high esteem by the New Wave. Lubitsch’s sophisticated comedies were held up for their exemplary screenwriting and perfect dramatic construction. Lang, whose later American films were generally felt by most critics at the time to be inferior to his early masterpieces like Metropolis and M, was defended by the Cahiers critics who pointed out that the expressive mise-en-scene of his German films had been interiorized in the intense Film Noir dramas he was now making in Hollywood. These later films such as Clash By Night and The Big Heat, they argued, were every bit as complex as his earlier works. Murnau, the director of masterpieces like Nosferatu and Sunrise, although largely forgotten by contemporary critics, epitomised for the New Wave an artist who used every technique at his disposal to express himself filmically. They sung his praises in the pages of Cahiers, and helped to re-establish his reputation as a cinematic visionary.

Another European influence on the New Wave was the Italian neo-realism movement. Directors like Roberto Rossellini (Rome, Open City) and Vittorio de Sica (The Bicycle Thieves) were going direct to the street for their inspiration, often using unprofessional actors in real locations. They cut the costs of filmmaking by using lighter, hand-held cameras, and post-synching sound. This approach enabled them to avoid studio interference and the demands of producers, resulting in more personal pictures. These lessons learnt from the neo-realists would prove a major factor in the success of the Nouvelle Vague ten years later.Roberto Rossellini

A number of American directors were also acclaimed in the pages of Cahiers du Cinema including not only well known directors like Orson Welles (Citizen Kane), Joseph L. Mankiewicz (The Barefoot Contessa) and Nicholas Ray (Rebel Without a Cause), but also lesser known B movie directors like Samuel Fuller (Shock Corridor) and Jacques Tourneur (Out of the Past). The Cahiers critics broke new ground when they wrote about these directors as they had never been taken so seriously before. They ignored the established hierarchy, focusing instead on the distinctive personal style and emotional truth they saw in these films.

By contrast, contemporary French cinema was a major disappointment to the New Wave group. The year that followed the Liberation of France saw the release of some outstanding films including Marcel Carne’sLes Enfants du Paradise, Robert Bresson’s Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne, and Jacques Becker’sFalbalas. However, since then, complacency had set in. There was none of the frank honesty of Italian neo-realism. Instead, most of the films that dealt with the war and the Resistance seemed to be sentimentalized versions of what had really occured. It was clear that the majority of people, including most French filmmakers, were not yet ready to confront the shame of the Vichy government and the many who had collaborated with the Nazis during the war.Rebel Without A Cause [1955]

...

In their articles, the young critics showed their disdain for the "tradition de qualite" prevalent at the time. Even directors who they had once admired like Henri-Georges Clouzot and Marcel Carne seemed now to have lost their ambition; content to play the studio game. Other directors with a more realistic style, such as Julien Duvivier, Henri Decoin and Jacques Sigurd, were equally disappointing; portraying a cynical view of contemporary society that was stylistically static and uninspired. For the New Wave cine-philes, who had expected so much after the war, it felt like a betrayal; and it explains why their attacks in print were often so vitriolic.

However, there were some contemporary directors who made personal films outside the studio system like Jean Cocteau (Orphee), Jacques Tati (Mon Oncle), Robert Bresson (Journal d’un cure de campagne), and Jean-Pierre Melville (Le Silence De La Mer), who were much admired. Melville was a real maverick who worked in his own small studio and played by his own rules. His example would influence all of the New Wave and he is frequently cited as a part of the movement himself. At the same time, the Cahiers critics praised certain French directors of an earlier era like Jean Vigo (L’Atalante), Sacha Guitry (Quadrille), and most of all Jean Renoir (La Regle du Jeu), who was held up as the greatest of French auteurs.

Auteur Theory

For the New Wave critics, the “concept of the auteur” was the key theoretical idea underlying their aesthetic viewpoint. Although Andre Bazin and others had been arguing for some time that a film should reflect the director’s personal vision, it was Truffaut who first coined the phrase “la politique des auteurs” in his article "Une certaine tendance du cinéma français". He maintained that the best directors have a distinctive style, as well as consistent themes running through their films, and it was this individual creative vision that made the director the true author of the film.Alfred Hitchcock

...

At the time auteur theory was considered a radical new approach to cinema. Before, it had been the screenwriter, or the producer, or the Hollywood studio, who was seen as the principle creator of a picture. The Cahiers critics applied the theory to directors like Alfred Hitchcock and Howard Hawks who had previously been seen as merely excellent craftsmen, but had never been taken seriously as artists. By uncovering the complex depths in the work of directors like these, the young writers broke new ground, not only in the way a film was understood, but in how cinema itself was perceived.Howard Hawks

Mainly as a result of this radical new way of looking at cinema, the reputation of Cahiers du Cinémabegan to grow. In Hollywood the review became essential reading and directors like Fritz Lang, Joseph Mankiewicz and Nicholas Ray were photographed with a copy of the magazine in their hands. Filmmakers like these weren’t used to people discussing their work with such accuracy and depth. They were deeply impressed by these young enthusiasts with their strong opinions and perceptive insights into the art of cinema.

Inevitably, as the ideas and writing of the Cahiers critics became better known, there was a backlash. The aggressiveness of the review was felt to be too extreme by some. It brought about a feeling of resentment, and even hatred, in those targetted. As a result a kind of warfare raged between the young radicals and the old guard of French cinema.

Short Films

The young group of writers at Cahiers du Cinéma were not content however, with merely being critics. They wanted to be filmmakers too. At the time there were two recognised routes to becoming a director. You could go through a long apprenticeship as an assistant director until, after many years, you were finally deemed ready to call the shots yourself. This approach was antithetical to the desires of impatient young directors with ideas of their own and a disdain for the conservative material they would have to work on.

The other method was to apply for a short film funding scheme. This government approved scheme ensured all films were made to a professional standard and was equivalent to a number of assistant positions. In the end, it enabled the candidate to obtain the work card needed to make features. Some of the older members of the New Wave began this way by making critically acclaimed documentaries: Georges Franju (Les Sangdes bêtes, Hôtel des Invalides), Alain Resnais (Night and Fog, Toute Le Mémoire du Monde, Le Chant du Styrene), and Chris Marker (Les Satues Meurent Aussi, Dimanche a Pekin, Lettre de Siberie), and Pierre Kast (Les Femmes du Louvre). Others soon followed their example including Louis Malle (Le Monde du Silence), Agnes Varda (La Pointe-Courte), and Jacques Demy (Le Sabotier du Val de Loire).Les Sang des Betes [1949]

...

The Cahiers group, however, rejected both of these approaches. They knew they would have to bypass the rules of the system if they wanted to break into the industry and make the kind of films they wanted to make. While still writing for the magazine, they gained experience and contacts. Chabrol worked as a publicist at 20th Century-Fox, Godard worked as a press agent, Truffaut worked as an assistant for Max Ophuls and Roberto Rossellini, and Rivette worked with Jean Renoir and Jacques Becker.

Sooner or later, though, they realised, if they wanted to direct, they would have to start by making short films, raising money anyway they could. Rohmer began in 1950, directing Journal d’un Scélérat, followed by Charlotte et Son Steak. Rivette, working with a script by Chabrol, directedCoup du Berger. In 1952 Godard directed a documentary called Operation Beton about the building of the Grande Dixene dam in Switzerland. He made the film with funds he earned by working as a labourer on the dam. After selling this, he had the means to make two dramatic shorts: Une Femme Coquette and Tous Les Garcons S’Appellent Patrick. As they gained experience, their films became more sophisticated. Rohmer made Bérénice in 1954, La Sonate a Kreuzer in 1956, and Véronique et son Cancre in 1958, to increasingly high standards.Les Mistons [1957]

...

Meanwhile, Truffaut had set up his own film company, Les Films du Carrosse, with the help of his wealthy new father in law, and in the summer of 1957, shot Les Mistons, based on a story by Maurice Pons. Pleased with the success of the film, its financial backer suggested he make another. Truffaut began making a short comedy set against the backdrop of the flooding that had been taking place in and around Paris at the time, but had trouble finding the right tone and handed over the footage he’d shot to Godard. Godard felt no obligation to follow Truffaut’s script however, and created an unconnected story with an off the wall commentary that broke all the conventions followed by traditional filmmaking. This film, Une Histoire d’Eau, was the most original, and most New Wave, of all the short films produced at the time.

Other important shorts made at this time, and in subsequent years, included Le Bel Indifferent (1957) by Jacques Demy, Pourvu Qu’On Ait L’Ivresse (1958) by Jean-Daniel Pollet, and Blue Jeans (1958) by Jacques Rozier. These were followed by by first films from Maurice Pialet (Janine, 1961), Jean-Marie Straub (Machorka-Muff, 1963), and Jean Eustache (Du Cote de Robinson, 1964).

New Developments

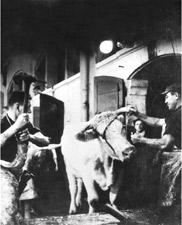

When the New Wave directors graduated from making short films to feature films in the late 1950’s, their ability to do so came about largely as the result of a combination of fortunate coincidences. Up until this time, filmmaking had always been an expensive business and it was necessary to have the backing of a major studio. Now, new circumstances came into play that enabled them to bypass this stumbling block.Truffaut and crew on location!

After the war, the Gaullist government had brought in subsidies to support homegrown culture. A further act, 1958’s "Constitution of the Fifth Republic", resulted in more money being available for first time filmmakers than ever before. Private investment money became more readily available and distributors were keen to back new directors.

At the same time, technological developments meant filmmaking equipment was becoming cheaper. New, lightweight, hand-held cameras, developed for use in documentaries, such as the Eclair and Arriflex were now available, as were faster film stocks which required less light, and portable sound and lighting equipment. These advancements meant filmmakers no longer needed a studio to make a film. They could now go out and shoot on location using smaller crews set against authentic backdrops. Working fast on low budgets encouraged experimentation and improvisation and gave the directors more control over their work than they might have had otherwise.

http://www.newwavefilm.com/about/history-of-french-new-wave2.shtml

No comments:

Post a Comment